Graduating high school at 16 is no easy feat. For Jessica Etter, it also meant the additional challenge of starting college at 17. Etter started her journey as an Oregon State University chemistry student with the goal of becoming a forensic scientist, however, she has since found a passion for research and will be starting a Ph.D. at Oregon State this fall.

As an undergraduate, Etter was heavily involved in research and did work looking at the anti-cancer properties of chemicals found in a food group that incites mixed reactions. Now as a master's student, Etter has started a project looking at how to quantify signs of Parkinson's disease in a person's blood.

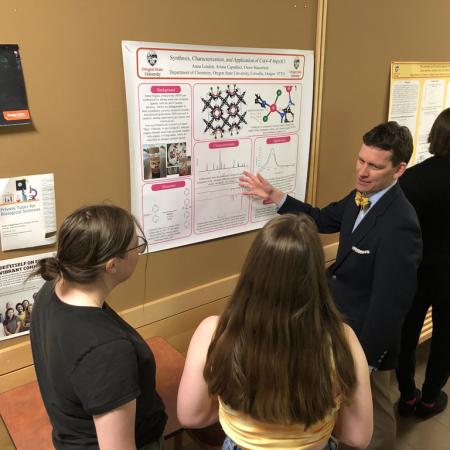

A long-time proponent of science communication, Etter has been involved in some form of science outreach since high school. She has continued to stoke the flames of passion for scientific outreach throughout her college career.

Looking Back

Born in California and raised in Scappoose, Oregon, Etter skipped the fifth grade, and graduated high school at the age of 16, in 2019. She started college that fall at 17-years-old.

Not yet legally an adult and only a few months over the age of 17, college came with unique complications. Navigating living away from family and new social dynamics while adjusting to college life and challenging academics was a huge undertaking.

Being younger than her peers drew Etter to the STEM Leaders program. The STEM Leaders program seeks to provide otherwise underserved students in science, technology, engineering and mathematics with the resources and experience they need to be successful in research.

"I would not have probably started research as early as I did if it wasn't for the STEM Leaders program," Etter said.

After she finished the program Etter worked for the program as an administrative assistant for two years. She found it rewarding to be able to share the positive experience the program gave her with others. She has since transferred to a similar program URSA (Undergraduate Research, Scholarship and the Arts) Engage. There she works as an Undergraduate Research Ambassador, a position she has been in for the last year.

Recently, she joined the Girls Empowerment, Engineering and Outreach club, which hosts STEM outreach events for the Corvallis community.

“That's been super fulfilling because I’ve always wanted to share science with people," Etter said. "I've been involved with science STEM camps since probably my first year of high school, so being able to continue that in college has been super amazing."

This summer Etter will be doing similar work through Oregon State's precollege programs. She'll be traveling around rural Oregon hosting the iINVENT science program for communities that traditionally don't have access to hands on science, technology, engineering and math opportunities.

While not quite science outreach, it was the science communications abilities and passion of her high school chemistry teacher that convinced Etter to major in chemistry in the first place.