For graduate student Jenna Bustos, crystals are the ultimate revealers of chemical truths.

Bustos studies radiochemistry, including elements such as actinides and technetium, as part of the Nyman Research Group at Oregon State University. Actinides are a series of rare radioactive metals, and unlocking their compositions takes different tools depending on their state of matter.

“Sometimes I seek to learn more about the speciation of the metals in solution,” Bustos said. “Are they small like a monomer, or big like a cluster? There’s a lot of instrumentation and characterization you can do to gauge this, including small-angle X-ray scattering.”

Small-angle X-ray scattering is a useful tool for determining the size and shape of species in solution, which has large-scale implications for the use of radioactive elements. “Insight into the bonding and chemical behavior of technetium and actinides is crucial to solving nuclear waste remediation and reprocessing challenges,” Bustos explained.

Understanding the ins and outs of these metals as solids, however, falls to crystals.

“Something I always say is that crystals are a chemist’s best friend,” she said. “When you crystallize something from a solution, it’s exciting because you can study it in the solid state. Crystals are powerful because they contain detailed information about the arrangement of atoms in chemical bonding.”

Although she may be investigating chemical bonds and representing chemistry at Oregon State now, Bustos had a long journey through education and research opportunities to become the chemist she is today.

A fateful meeting

While growing up and attending college in New Mexico, Bustos became familiar with radiochemistry through the large presence of Los Alamos National Laboratory. Los Alamos is a government laboratory with a concentration in national security science, and its well-known work with radioactive materials introduced Bustos to the field. Despite this, the actinide metals that are now essential to her work played a surprisingly small role in her earlier education.

“When I was studying in undergrad, my favorite class was always inorganic chemistry,” she recalled. “I remember asking my professor, ‘What’s that block of chemicals at the bottom of the periodic table?’ referring to the actinides. He said, ‘Don’t worry about those, chances are you’ll never work with them in your entire career,’ and now my entire career is centered around that block.”

Not yet knowing this would be her path, Bustos began seeking out potential universities to continue her education as she neared the line between undergraduate and graduate school. During her search, she attended a scientific conference that would change her life.

“It’s fascinating how there’s so much more to radiochemistry and actinide chemistry than what the public perception of it is.”

In 2019, the Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS) hosted a conference in Honolulu, Hawaii. Hoping to network, Bustos made her way through rows of university recruiters and research presenters before stumbling upon Oregon State professor May Nyman. She was quick to accept when Nyman invited her to a symposium on actinide science. Although she knew of the general field, Bustos found that the symposium revealed a depth to it she hadn’t seen before.

“When you first hear about radiochemistry and actinide chemistry, it can have a negative view to it because people associate it with nuclear waste. So as an undergrad not exposed, that’s what I went into the symposium thinking,” she said.

To her surprise, the event shared a different side of the discipline. “It was very interesting to see the fundamental chemistry behind it and how extraordinary these elements are. It’s fascinating how there’s so much more to radiochemistry and actinide chemistry than what the public perception of it is.”

After meeting Professor Nyman and learning the Oregon State program is affiliated with the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), Bustos was eager to join the Nyman Research Group on campus. Following her acceptance into the university in 2020, she did just that.

Pedal to the metal

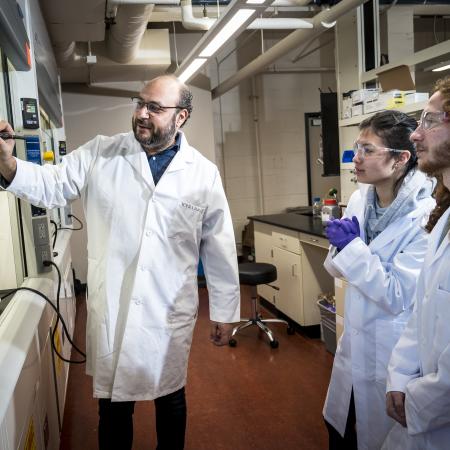

Unfortunately, she would have to wait before donning her lab coat and goggles. The swift spread of COVID-19 saw her journey at Oregon State begin in isolation, with her work limited to mathematical aspects of research that could be done outside of a lab. Once being in-lab became viable again, Bustos started experimenting with radioactive materials — actinide metals in particular — just like the researchers that had inspired her at the symposium.

“I was really excited to come work with Professor Nyman after hearing her talk at the conference in 2019,” she shared. As the lab kicked into full swing, it increasingly felt like the right place for her to be. “With Oregon State as a whole, it’s great to find your community here. The chemistry program has been really amazing.”

While starting her research, Bustos quickly discovered that discerning the behaviors and makeups of these materials was not as simple as finding those of non-radioactive alternatives.

“To work with radioactive elements you have to work with a non-radioactive surrogate that is similar to what you intend to use,” Bustos explained. “For example, I work with the non-radioactive element rhenium as a model for technetium, and whatever works with rhenium I scale down and use with technetium.”

Over the following years, Bustos’ role in the Nyman Research Group gradually shifted. While she still regularly experiments with radioactive elements, she has also become a mentor for newer members of the lab and does outreach on behalf of Oregon State.

“I’m now one of the more senior people in the group, so I help incoming group members adjust and get familiar with the lab. Recently, I was also recruiting for OSU by introducing prospective students to the university and acquainting them with these opportunities that I’m fortunate to have received.”

Full-circle and beyond

Bustos’ work recently culminated in an internship at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 2022. She was given the opportunity to stay at the NNSA national lab over the summer and take part in their research. “In a nutshell, I studied actinide mobility in the environment,” she said. The internship saw her examine how actinides move through the environment and interact with organic matter in order to travel, which can lead to radioactive contamination.