Shaping challenges into opportunities is what chemistry Ph.D. student Abdikani Omar Farah has done nearly all of his life.

Before moving to the U.S. at 16, Farah spent his childhood in East Africa, experiencing firsthand what it meant to lack access to medicine. This scarcity was a common problem in the villages he lived in, and seeing his community in need became the driving force behind his pursuit of a career in chemistry.

Now that he has earned the 2023-24 Larry W. Martin & Joyce B. O’Neill Endowed Fellowship, Farah plans to push forward in computational organic chemistry at Oregon State and continue reaching towards his ultimate goals as a scientist.

Pursuing an impact

The fellowship was founded in 2018 by math and engineering alumnus Larry Martin and his wife, Joyce O’Neill. Graduate students within the College of Science whose research involves computational modeling are eligible to receive the award.

Farah collaborates with leading organic chemists around the world to better understand chemical reaction mechanisms and investigate factors that influence the selectivity of reactions.

In organic chemistry, enantioselectivity describes when a reaction preferentially forms one product over another. One area of Farah’s research is understanding certain enantioselective reactions that are crucial for drug synthesis. He and his colleagues utilize computation, especially density functional theory (DFT) methods, to determine the transition state structures of reactions they study and build models that explain the origins of a reaction’s selectivity.

He has found great success in his research, having published five papers in renowned chemistry journals and currently being in the process of a sixth during his third year at Oregon State. The fellowship, he says, will be a great help as he continues to earn his Ph.D., a critical step for his future plans.

“I loved it because I knew that the drug I made was going to treat a person. That is a rewarding experience, knowing I myself could one day need that drug, or a loved one, or a colleague or a friend.”

Before coming to Oregon State for graduate school, Farah worked as a process and developmental scientist at a pharmaceutical company in Wisconsin. His work aimed to streamline how vital drugs were mass-produced, which he found purpose in.

“I loved it because I knew that the drug I made was going to treat a person,” he said. “That is a rewarding experience, knowing I myself could one day need that drug, or a loved one, or a colleague or a friend.”

Although he felt a calling for discovering new drugs and refining development processes for existing ones, Farah knew his position wouldn’t allow him to make choices outside of how the drugs were made, such as their cost.

“As someone who came from a community that these drugs will impact heavily, I felt like I needed to be a voice in the decision-making,” he said. This desire to have more influence meant he would have to earn a Ph.D., which led him to continue his education at Oregon State.

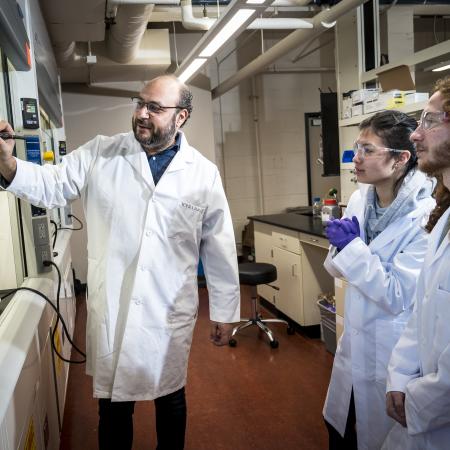

When he arrived, Farah joined Professor Paul Ha-Yeon Cheong’s research group to study computational organic chemistry. The lab strives to explain what causes selectivity in complex organic reactions using computational analysis.

While he was excited by the professor’s research, it was ultimately their shared commitment to paying forward the opportunities given to them that convinced Farah to join the group.

“There’s this constant belief that Paul has — and I would like to think that I embody — which is that opportunities are rare, talent is abundant. You can be a child in South Side Chicago, in the Himalayas, in the Amazon or in the Sahara Desert, and you can already have natural-born talent. But opportunities that are available for all those children are rare, and when it is given to those kids, they can be anything. Paul and I strongly believe that we create those opportunities for others,” he said.

“That will be my life goal. I know a lot of things that we do are temporary in life, but I would like to contribute to giving more people educational opportunities in the place that I come from and the communities that I’m in now.”

Farah wants to someday play a part in creating institutions and nonprofit organizations that could provide more education to communities in East Africa. To further help through science, he is also working toward not only creating better medicines in the drug development industry, but being in a position to lessen their cost so they are more accessible to these communities, as well.

Raising the bar and paving the way

Outside of financial contributions to academic organizations providing educational opportunities in East Africa, Farah hopes that his successes can be proof of what is possible for others and inspire the next generation of scientists in the region.

For people of color and other minority groups, Farah says, not having visibility in a field makes the barriers into it even larger. By earning a Ph.D., he would like to pave the way for many more to follow.

“If someone like you can do it, so can you,” he said. “I would like to think that I’m raising the bar for the next generations, for my younger siblings and my nephews and nieces and all the people that look like me … I don’t think we know anyone in my tribe that has a Ph.D., so I might be the first one, but I hope I’m not the last one.”

“It’s not just working hard, but also knowing the reason that you’re working hard. It doesn’t matter how well you paint if you’re painting the wrong wall.”

Farah emphasizes the importance of having a purpose beyond strictly science. One of the key ideas he has taken from his time in chemistry is learning what impact he wants to have on the world through his career.

“It’s not just working hard, but also knowing the reason that you’re working hard,” he said. “It doesn’t matter how well you paint if you’re painting the wrong wall.”

Knowing what gives his work meaning, Farah is eager to continue pushing his research and giving back along the way.